The Biography of Professor Peter Ozo-Eson(1)

Marc Antony, in his funeral oration at the burial of his bosom friend, Julius Caesar, says thus: “We are here to bury Caeser, and not to praise him….the evil that men do, lives after them, the good often interred with their bones!”

Marc Antony through the use of irony speaks to the immortality of evil and the fickleness or maliciousness of the human mind by way of a compulsive preference to remember or project one’s mistakes over good deeds.

He also speaks to the triumph of good over evil in the long run, despite this inherent human frailty and manipulations by institutions of power, as subsequent events in Julius Caesar , arguably Shakespeare’s most popular play on power and politics, would reveal.

Today, we are here gathered in honour of one of our own, a great patriot, an uncommon scholar, an orator with equally writing skills, a courageous administrator, an eagle-eyed researcher, a hard-nosed interrogator of ideas, a persuasive debater, an ideological pugilist with clarity, an adoring family man, Professor Peter Ozo-Eson’s contributions cannot be extinguished by time or space, even malice.

We are here to not praise him or bid him farewell, for in all sincerity, we cannot part company from one whose ideas live in us, live with us and whose mentorship abides, whose honesty and commitment challenge the best in us…..one whose baritone at the negotiating table put the social partners on their toes, one who neither jittered nor dithered on a worker-cause, one who never curried favour. We are to state the facts as we know them.

We are here to celebrate the life and times of Professor Peter Ozo-Eson and I urge all of us to be strong as we reminisce.

Professor Ozo-Eson was of nobility even though you’d never catch him say such ‘heretic things’ as that would constitute a betrayal of his ideological belief of the equality of all humans irrespective of the circumstances of their birth.

Rather, he was more concerned about the nobility of character which he lived illustriously, often in denial so others could be safe or comfortable.

He lived a qualitative life in spite of his sparse resources. He extended same quality of treatment to friends without a word of it to third parties. His generosity knew no bounds.

He was a man of remarkable courage and strong convictions. Once convinced on a cause of action, for him, there was no prevarication or turning back. This character trait influenced his attitude to his declining health. He confronted it headlong with an uncommon stoicism and with all the resources at his disposal in and outside the country. Often, he was the one urging others to be strong, reassuring them he’d pull through.

Over the decades and in spite of the risks associated with his views, right from his undergraduate days, and detention spells, he was a quintessential family man who never missed a good opportunity to indulge or celebrate with loved ones.

But who is (not was) Professor Peter Ozo-Eson?

The Biography of Professor Peter Ozo-Eson(2)

Time and space are apparently limited for a comprehensive response to this question. Accordingly, one can only offer a glimpse of the life of this man, passionate about excellence and justice.

Peter Ozo-Eson was born on

June 29, 1948 to Pa Enehizena Ozo Eson and Ma Imalele Eson of Uselu in

Benin City.

His beginnings were humble as with most people of his generation, but unlike most people of his generation, he had prescient parents who saw tomorrow, and who believed that the future lay in the acquisition of western education, little of which they themselves had. More remarkably, he had parents who refused to be bound by the limiting or constraining powers of material poverty and therefore sent him to school in spite of the prohibitive cost of education.

He also had the rare fortune of a mother who would spend days in the bowels of the forest harvesting fuel wood for sale in order to pay his school fees, and in equal measure, a father who was even ready to put up for sale, his only house to enable him pay his and his elder brother’s school fees.

We have had situations where by default or otherwise, the commitment of parents is not marched by the commitment of the child for whom heroic sacrifice is made. In his case, however, the overwhelming support of his parents was amply rewarded by a son who not only took seriously his studies, but was indeed precocious and thus from the beginning performed exceedingly well academically. For parents and child therefore, there was mutual respect, silent appreciation, an unspoken love, a bond, an unbreakable bond, especially between him and his mother.

This was to play out later in his life when the news of the death of his mother in relative old age was broken to him on a high way in Lagos. He was inconsolable. However, this would not be the only time his emotions would betray him. In spite of his stiff upper lip mien and starchy carriage, he broke down again while reading a tribute in her honour during her rites of passage. The children sometimes in their mischievous moments taunted him with this. But today, it is their turn!

However, soon enough, the bond between him and his parents was to be threatened as the son set out to be a Catholic priest against their wishes as they felt celibacy would deny them, in some way, progeny. However, the son had his way and proceeded to Saint Paul’s Seminary, Benin, but providence had other designs.

The overbearing attitude of the Irish priests which sometimes bordered on intolerance and racism, provoked a major revolt leading to the chasing out of the priests from the seminary by the irate young seminarians. It took the intervention of the Church and the police to restore peace. Not unexpectedly, there were dire consequences, as wanton suspension and expulsion of students followed.

Although he was not among the victims due to the absence of direct evidence against him, an altercation between the senior class (on which behalf he spoke) and the Rector, provided the needed ammunition. The Rector physically dragged him before the Bishop who directed that he be placed on indefinite suspension until he purged himself of his sins!

A heart-broken Nigerian priest in the seminary on learning of Ozo-Eson’s predicament, wailed, “…you are stupid, you played into their hands…they do not want intelligent Nigerians to become priests!” He nonetheless offered to intercede on his behalf with the Bishop. He was still awaiting his recall when Biafran soldiers under the command of Colonel Victor Banjo, overran Benin. This was in 1967.

When the federal soldiers liberated Benin a few weeks later, St Paul’s Seminary was one of the places they sacked on the suspicion that some of the Reverend Fathers co-operated with the invading Biafran troops. The damage was so extensive that the final year students were sent to the seminary at Ibadan to continue their studies. This was when he was recalled. However, the period of suspension had availed him the opportunity to come to the conclusion that priesthood was not his calling.

A year later, he was again contacted to return to the school preparatory to his being sent to a university in Rome based on his performance in the London GCE which he sat as a private student, but he declined the offer.

He ended up as a classroom teacher at Ishan Grammar School, Uromi, where he taught sundry subjects and from where he supported his elder brother who was an undergraduate student at the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. Although he had all it had all it took to be in school himself, both of them could not afford the cost. However in his final year, his elder brother encouraged him to apply, telling him they could rough it out together in that one year. And based on his brother’s advice, he applied to the five universities then: UI (Economics); ABU (History); UNILAG (English Language); UNN (Business Administration), and Ife (Estate Management).

All but the University of Ife offered him admission but he ended up reading Economics at the University of Ibadan (UI) not because he preferred the course to the others but on the popular advice that UI was the premier university.

However, the excitement of being an undergraduate was short-lived as he had no resources to pay the fees for the next term after the first. He lost his accommodation and the means for feeding on campus where no cooking was allowed. He was therefore technically a destitute. Faced with the prospect of self-rustication, one friend offered to share his bed space, another offered his meal tickets!

However, things were to change dramatically in the second year as his elder brother had not only finished his studies, the Ahmadu Bello University in acknowledgement of his brilliant performance, had offered him a teaching appointment in the Geography Department.

Coupled with support from his brother, he had won two scholarships: the

UAC scholarship which took effect retroactively from his first year, and the University scholarship based on merit. Both ran the entire duration of his course.

In spite of his privations in his first year, he was deeply involved in students union politics right from the beginning to the end of his academic career. As Deputy Chairman, he led the UI delegation to most NUNS meetings and activities. As young student activists, they brimmed with enthusiasm and were ideologically focused. They were deeply involved in the national and international discourses of the time: liberation struggles, political ferments, economic independence, industrialisation, etc. On occasions they engaged the Gowon administration on issues of corruption and the conditions around the National Youth Service Corps of which he was second set. They demanded answers! They demanded solutions!

He was so involved in student union activism that some of the students from his ethnic group had to call him aside for caution. “Be careful, you are too active, don’t endanger the investment of your parents”.

1974

The Biography of Professor Peter Ozo-Eson(3)

Much later, they were to tell him, “Aaaaaaahhh, we didn’t know you had the capacity to combine all this your activism with academic work and still excel!” These were among his most cherished moments in life.

On graduation in 1974 with B.Sc (Hons, 2nd Class Upper Divsion), he was conferred with the Isaac Dina Memorial Prize in Economics for being the best graduating student in Public Finance. Jobs poured in from choice companies, and arguably, some of the best government institutions but he turned down all the offers because his interest was in the academia. Not unexpectedly, he accepted the offer of Research Assistant at NISER which was then part of the University of Ibadan.

However, when he was offered a merit-based scholarship by the UI alongside some of his colleagues who had performed exceptionally well in their final year examination to do their post-graduate studies in Nigeria, he politely turned down the offer.

In September 1975, he secured admission to read Energy Economics at the University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, but did not have the requisite financial capacity, and therefore could not take up the offer. On getting to know what his challenge was, the University wrote explaining to him that the Master’s degree programme in Energy Economics was highly competitive in the university and that a balance was struck between the competing intetests including OPEC, oil majors, etc, and that he was the only one admitted from the OPEC countries. In order to maintain this balance, the university offered him a full scholarship, provided he could resume in the Winter Semester in January of that year.

However, all of that came to naught as the government of his own country denied him a passport. His sin was that he had made comments during the commemoration of Kunle Adepoju Day two years earlier that the authorities were not comfortable with. He lost the scholarship and everything that came with it. However, he quickly put this behind him this loss determined more than ever before that the malevolent behaviour of the state would neither cow him nor make him miserable as that would amount to admission of defeat.

While on a one-year programme at the UN Institute for Development Planning in Dakar, courtesy of NISER, he was offered a scholarship by the Bendel State Government to Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada, for his Masters and Ph.D.

In the run up to his departure from Canada after successfully completing his course of study, a team from a reputable Canadian university asked him out to lunch at which he was offered a job as Assistant Professor in International Trade. His response stunned his hosts as he told them bluntly: “You are very interesting people. I came here as a foreign student. You made me to pay differential fees as a foreign student. And here now, I am finishing, and you want me to stay back and develop your country. My country needs me more”. Case closed!

What made this strand of patriotism even more remarkable was that many a student who had finished their programmes were looking for ways and means to prong their stay or even stay back. His wife to whom he got married in Canada was yet to finish her degree programme. His acceptance of their offer would have availed her the opportunity of rounding up her studies.

But this would not be the only time he would be spurning a juicy offer in order to serve his country. In 1988/89, he had won the post-doctoral commonwealth fellowship that took him to Brighton, Sussex, at the end of which he was offered a job by Africa Books Limited. He said, “No”, in spite of the fact that the operating conditions at home were highly unfavorable. Indeed, that era witnessed the worst case scenario of mass exodus of academics, in response not only to the vagaries of SAP (Structural Adjustment Programme) but the intolerable conditions in the campus.

Thus, against the tidal flow, he returned to Nigeria, to the University of Jos in 1982, to his first love, the academics, brimming with optimism, idealism, hope and faith.

Looking back years later, he would say the happiest moments of his life were in the campus, both as a student at the University of Ibadan and as a staff at the University of Jos. His inspiration were his lecturers, particularly, Professors Bade Onimode and Omafume Onoge, and the free and unfettered environment that the campus provided for intellectual discourse, inquiry and activism .

But he may have overrated the campus environment as subsequent events would prove. These operated at both the university and national levels. At the university level, alongside other progressives, he engaged the university administration based on principles to ensure things were properly done, that there was social justice for all, that students were not unduly rusticated or expelled for their views or beliefs, that there was strong internal governance culture, and above all, that the university was developed.

The contestation pitched him against the Vice Chancellor who came from Benin as himself, and soon, pressure came from the Benin Community that he was waging war against his own. Part of the terms of armistice by this people was that he should accept an arranged movement from the University of Jos to another university. He declined the offer, and from then on, he was a marked man.

However, the privations he suffered as a result of this did not hurt him as much as the backstabbing he received from some of his comrades with whom he was in the trenches. Some of them had said behind his back that he was favoured by the Vice Chancellor because they were of the same ethnic stock. And that if it were any other person that had headed the opposition against the VC with such intensity and consistency, such a person would have been long dismissed. This was quite unnerving for him.

There was another level of contestation in the university. Because of his insistence on procedure and quality, he was dubbed anti-catchment area, yet he had no such intentions. This inevitably undermined his relationship with some of his colleagues on the left. Luckily, one of the Vice Chancellors understood much later that his positions on issues in the campus were strictly based on principles. Even the Vice of his ethnic group, years after he had left the university, openly acknowledged him as a man of principles and a man of honour. A third Vice Chancellor, while making up to him said that his greatest regret was in allowing others to choose his enemies for him.

In a nutshell, therefore, the three Vice Chancellors under whom he suffered persecution all came to appreciate his worth later as a man of value, a man of substance and a man of honour. The other point to note is that the persecution he suffered for so long did little or nothing to make him change his views about life or his commitment to the cause.

Remarkably, his regret remained not the price he had had to pay for his views but in allowing other people’s attitude to bother him for so long to the extent that it created unnecessary tension, and from unnecessary tension to certain decisions!

At the national level, the man got involved in union activities, the Academic

Staff Union of Universities to the extent that he got elected as National Internal Auditor in the presidency of the late Professor Festus Iyayi. In the years that followed, he was actively involved even when he no longer held a formal position. For instance, he was deeply involved in the negotiations that culminated in the 1992 agreement which was preceded by strikes. During that struggle he was forcefully ejected from his official accommodation at the University of Jos. His things were thrown into the street, and for one month, he and his family had to take refuge in a oneroom apartment provided by his wife’s employers. However, the height of state harassment was to come under the Abacha regime when during one of the ASUU strikes, he was arrested and detained in very unsavory conditions for seven days.

However, rather than break him, this hostile treatment provided him the needed opportunity of conscious indoctrination of his children whom he often told that it was the price they had to pay for commitment, and they understood. The political consciousness of his dear wife provided a great source of support at these times. On his own part, their understanding reinforced his stoicism and the strength to carry on.

In the course of his activism in ASUU, there were land-mark interventions directly traced to him. For instance, in 1983, when ASUU resolved to affiliate with the Nigeria Labour Congress, he was the one chosen to move the historic motion in the presidency of Dr Mahmud Tukur, even though the leadership of the delegation from the University of Jos was vocally against such affiliation.

Of course, government not only annulled this marriage, it went on to proscribe ASUU. In the intervening period, government sought to obtain a World Bank loan to fund tertiary education. The loan was going to be used to buy books and other learning aids. However, serious-minded academics like himself, felt this portended grave danger as it would inevitably impose the American view of the world on our education system with all the fatal consequences.

Although ASUU was still banned, committed academics worked surreptitiously, assiduously and clandestinely to oppose the taking of this loan.

Consequently, a conference was called at the University of Ife at which he was commissioned to do a paper entitled, “Funding of Higher Education in Nigeria: A Cost Benefit Approach”. In the paper, he provided the theoretical framework for the need for private sector companies and enterprises to contribute to the funding of higher education. This became the basis of which ASUU fired a memo to the Longe Committee set up by government. The Longe-Committee recommendation and the subsequent 1992 ASUU-FGN Agreement led to the establishment of the Education Trust Fund and the institution of an Education Tax.

Today, after embellishments, it is known as TETFUND, an organisation that has touched the lives of public universities in no small way.

Ozo-Eson’s activism went beyond the four walls of the university. Aside from regular commentaries on matters of national importance in the mass media, especially the electronic media, he was involved in major engagements such as the anti-SAP/ IMF campaigns. As part of his contribution to this very campaign, he did a two-part documentary of one hour length each in collaboration with Mathias Igbaruma (now of blessed memory), a friend on the staff of NTA, Jos.

The first part was aired successfully before all hell broke loose. The tapes were confiscated and the staff of the NTA all but lost their jobs for “waging a campaign against government’s position”. Much later, and based on the first tape alone, people used to stop him on the street to say everything he had said about SAP had come true.

Despite the set-back of losing his tapes, both the edited and non-edited copies, he continued with his regular public appearances. This was to pay off as his transition into full union work could not be divorced from these public appearances. Although his activism at both local and national levels had brought him in contact with some affiliates of the Congress , it was Comrade Paschal Bafyau, then President of the Congress who strolled into his house on this fateful day unannounced at the University of Jos to say, having watched some of his discussion programmes on TV he was inviting him to give a lecture at their facility in Kafanchan. This was how it started.

Years later, he did a year sabbatical at the Textiles Union under the watch of Comrade Adams Oshiomhole with whom he had developed a robust relationship. His love for union work blossomed. One thing led to the other and he was head-hunted by the Nigeria Labour Congress where he formally resumed as Director of Research in 2003 during the presidency of Comrade Adams Oshiomhole, where he continued to give intellectual direction to the organisation. Aside from giving intellectual direction, he brought added value, fresh insights and punch to the job, especially during negotiations.

Earlier, he had taken a leave of absence from the University of Jos to serve as Director of Projects (and later Acting Executive Director) at the Centre for Advanced Social Sciences (CASS), PortHarcourt between 1998 and 2003.

Although he had little or no political ambition, he was unanimously appointed General Secretary in 2014! In 2019, he he retired from the services of the Congress after rendering unquantifiable and immeasurable service.

Dr Ozo-Eson has produced generations of professors, has published seminal papers in reputable journals, made robust interventions in public and porivate debates, as well as livelied up board rooms. Indeed, negotiations were seldom concluded without the familiar ring of his voice.

A widely travelled man, in the course of his career he had served in a number of critical committees and boards including the National Economic Council; the Presidential Study Group on the Monetisation of Fringe Benefits in Nigeria; the National Economic Intelligence Committee; Petroleum

Products Pricing Regulatory Agency (PPPRA); and National Salaries Incomes and Wages Commission.

An avid lover of football and lawn tennis, he plays table tennis and lawn tennis.

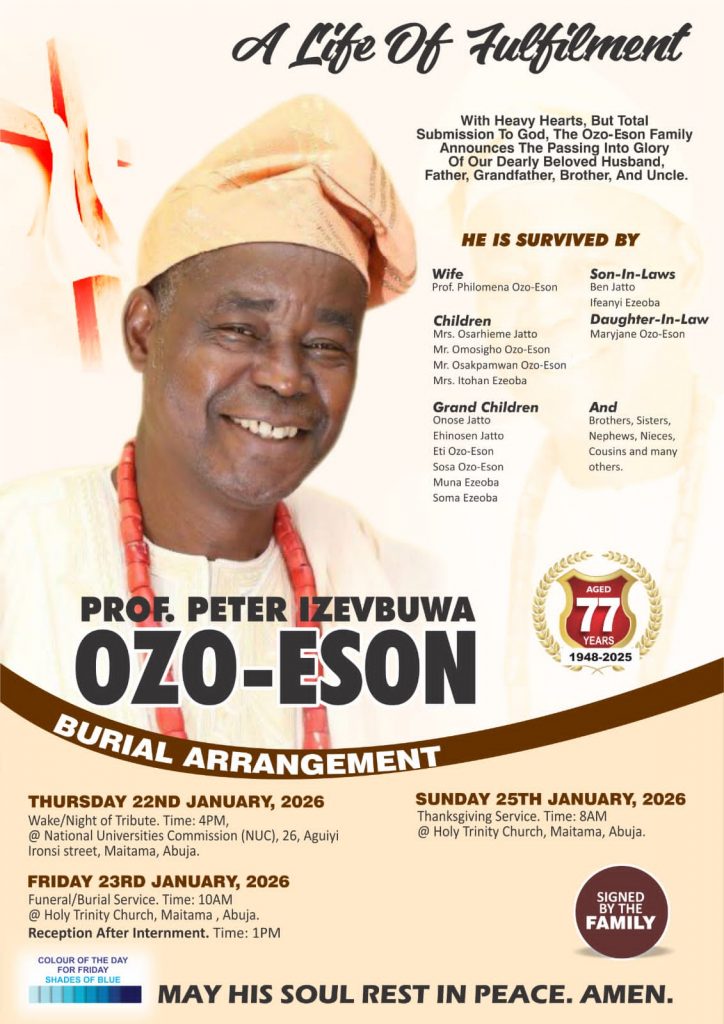

He passed away on December 13, 2025 surrounded by family with whom he was chatting.

He is survived by his heartthrob, Professor Philomena Ozo-Eson and four lovely children:

Mrs Osarhieme Jatto;

Mr Omosigho Ozo-Eson;

Mr Osakpamwan Ozo-Eson; and

Mrs Itohan Ezeoba.

He is also survived by grandchildren, cousins, nephews and other extended family members.

I’d end this tribute with Marc Antony:

“He was my friend, faithful and just to me. My heart is in the coffin in there with [him] “.

Distinguished invited guests, ladies and gentlemen, let us all rise in honour of this warrior, titan and icon, a scholar’s scholar, a robust intellectual, a symbol of academic excellence, a distinguished Nigerian, an uncommon patriot, an unyielding unionist, a hard-nosed negotiator, a man of strong convictions with marks to show for them, a man unfazed by persecution and gales of life!